… and what does it matter? |

Hold on to something, this one is going to jump around a bit…

A lot of the feedback on my last offering (‘Body Modification’?) gave me a sense of preaching to the converted. That is, of those who commented, the majority thought the points I was looking at were ones they agreed with and found to be rather obvious. While it is nice to know that others share something of my view, I can’t help but be dogged by a certain uneasiness. If it is true that many modified people will agree that body modification is something everyone does and includes things like haircuts and possibly even clothing then why isn’t that reflected in their words and behavior?

It reminds of the problem with evolutionary theory. Many people will accept and recite back evolution when questioned as to the nature of the human animal but they do not reflect this position in how they actually behave. It is simply a ‘fact’ that they have learned to give in response to certain promptings but it is certainly not what they base their actual decisions upon. People who purportedly believe in evolution hardly ever react to and judge human behavior on the grounds that human beings are a domesticated primate group. If they did so, then much of our moral and social quibbling would be absolutely absurd. There is a clear gap between what many people say they think and how they actually behave on this issue and it shows up in much the same way for modified people talking about modification.

“The difference between people without tattoos and people with tattoos is that people with tattoos don’t mind if you have tattoos or not.”

I have seen variations of the above in many a shop, on t-shirts, and quoted by people complaining about the fact that the ‘un-modified’ often discriminate against or look down upon them. However, I often see behavior which goes directly against it — people with tattoos or other mods being very judgmental and pejoratively discriminating against those without. This is not only the case for people without what is popularly referred to as body modification but also for those with ‘taboo’ mods like facial tattooing or amputations. While I find it unfortunate and potentially damaging that people who choose certain methods of body modification (like tattoos or piercings) would further divide themselves from people do not, rather than try and show those others that what they do in getting tattooed or pierced is simply another means in a process we all engage in, it seems even worse to me that they should want to divide amongst themselves those with acceptable and unacceptable tattoos, and so on. For anyone doing so and then claiming to understand body modification as a more general term I would like to hold up the mirror of logic so that they can clearly see it shatter with their reflection.

This does lead to another interesting trail of thought, and one that Shannon suggested investigating as part of following up the piece: the differences between atypical and mainstream modification and how the line is drawn. Quite clearly this is a question of relative cultural and social values as it can be seen that what is the norm in one part of the world and a given subset of a population can vary widely and be plainly contradictory with another. For example, in many African cultures scarification would not be atypical while in the US it is still anything but mainstream and while tattooing might still be considered atypical in the US for the culture as a whole, in many subsets (like the often cited bikers and rock musicians) it is very much part of their mainstream, if not obligatory. To push it back to a broader context, we could ask why is it that I am allowed, and often expected, to cut and style my hair but I am frowned upon for doing so in certain ways (such as a Mohawk)?

As a side note, if you want to really see how something like hair style can affect your life try wearing a moustache in the style that was chosen by Hitler (and was very common in its day). I wore such a moustache for a few months years ago and was almost universally reviled for it, receiving harsh and negative reactions the likes of which my facial tattooing has never even approached. All for a small patch of hair that was representative of nothing symbolic but just a silly experimentation to see how it looked. (When people would call me nasty names I would rebuke them for not appreciating my homage to Charlie Chaplin‘s genius — this generally just confused and further incited them).

To really address why some modifications are accepted and others are less accepted or even taboo would require an indepth examination of the relevant culture or society. I am certainly not going to attempt a full deconstruction of Western civilization and its views on the body here — others have attempted and I think pointed to a great many salient points and influences. I do think though that what you see in terms of a given group’s attitudes towards hair, dress, tattoos, elective surgery, and so on is something of an admission that body modification is a universal and as such rather than be denied, it can hopefully be directed for the good and interests of the group. We then see the typical problem arising on the macro scale that the group is simply too large and diverse in many cases to reach fundamental decisions (for example, an ear piercing on a man in an urban area of the US will have little effect but I still know and see many regions in which it draws negative attention).

Another jump: mainstream versus atypical puts me in mind of another term: extreme. What is extreme body modification? Most of the treatments I have seen before propose that there are two grounds on which a modification can be extreme: technical difficulty and social reaction. Personally, I think the former can be almost completely discounted. The technical difficulty of a modification (now speaking in the popular sense) is negilible and for the most part only exists because of how the industry is structured. I do not mean to deflate anyone but the most complicated procedures being performed by modification artists (such as implants, genital splitting, urethral relocations, and minor amputations) are incredibly basic compared to what is done on a routine daily basis by the medical community. It is the social component that makes something truly extreme in my opinion primarily because it is a social stigma held by those most qualified (doctors and surgeons) which prevents us from attaining the true outer limits of what is possible in terms of modifying our bodies.

Given the possibility that what is extreme is socially derived it will then be quite relative. As has been pointed out before, for a given pair of individuals it may well be a more extreme act for one to simply dye their hair than it would be for the other to tattoo their face. I had a friend from a very traditional Japanese family in college who was nearly disowned for coloring her hair red whereas I received a primarily positive response from my family when I tattooed my face. And what about facial tattooing?

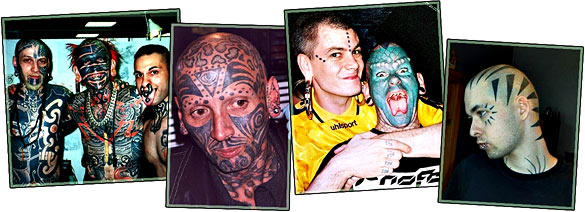

Recently on IAM, Shannon predicted and described facial tattooing as the next “trend”. I have to agree that I have seen and been approached by people considering it a lot more in the past couple years but I would emphasize the caveat that it’s going to be a certain type that really becomes predominant (remember what I said above about groups attempting to direct modification for their own good and interests).

I think you will see people who have always been a bit further along (full body suits, heavy facial piercing, etc) realizing that in today’s world they aren’t really taking that much of a risk by moving into facial tattooing — If you already have large stretched or many multiple facial piercings the general public’s reaction if you add a facial tattoo probably won’t change that much. The ones that I think are interesting from the standpoint of cultural change are those that are less heavy (full black or green, heh) designs — ones that work up the neck or along the hairline and are more decorative than transformative of a person’s appearance. All that said though, a couple things about facial tattooing (inspired in part by Cora’s column on things to consider for those considering the incredible transformation she is undergoing):

- It will change your life. The degree will vary but it will change and you will not be able to predict a lot of it.

- Make sure your life is at a relatively stable point. Getting your face tattooed is not an answer or a fix to anything. It is going to make your life less certain (see above) and that’s not something you need to introduce if things are already at all shaky.

- Make sure you want it and get what you want. Seems obvious I know, but it is amazing what people overlook or skimp on.

- Tell people you care about beforehand and examine their response. They will be your support and can help you a lot. Sometimes people are amazed that I have such a good relationship with my family but as I often say (and mean it every time) I couldn’t do what I have done without them.

- Try it out first. Use makeup or whatever to simulate it — not just for a minute but for days or longer. Put the design up and look at it everyday because once it’s there you will have to see it everyday.

In a perfect world, I would suggest these (and more) before any mod but I’m not silly enough to think that’s going to happen…

because the world NEEDS freaks… Former doctoral candidate and philosophy degree holder Erik Sprague, the Lizardman (iam), is known around the world for his amazing transformation from man to lizard as well as his modern sideshow performance art. Need I say more? Copyright © 2003 BMEzine.com LLC. Requests to republish must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published June 26th, 2003 by BMEzine.com LLC in Tweed, Ontario, Canada.

|