| The Gift of Magnetic Vision |

Maybe technology eventually turns them into something that we wouldn’t call human. But that’s a choice they make — a rational choice.

– Bruce Sterling, Schismatrix

|

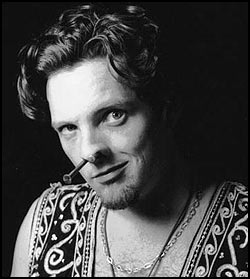

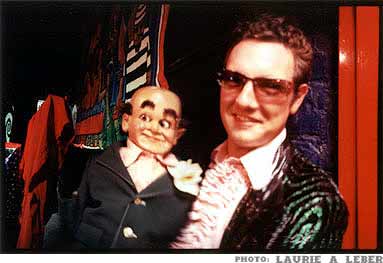

It’s hard to deny that Steve Haworth (iam:steve haworth) has been one of the most influential and innovative voices in body art over the past decade. In the field of implants as sculptural art he has singularly defined the art form, and with the assistance of Jesse Jarrell (iam:Mr. Bones) has continued to escalate it into increasingly refined forms. I heard a rumor recently that they’d been experimenting with magnetic implants, and I thought to myself, “cool party trick”, and checked out the pictures on Steve’s page.

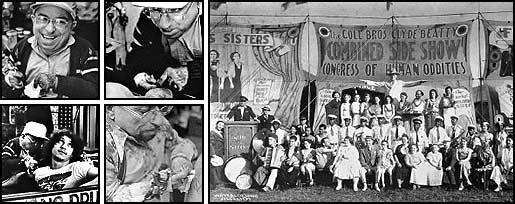

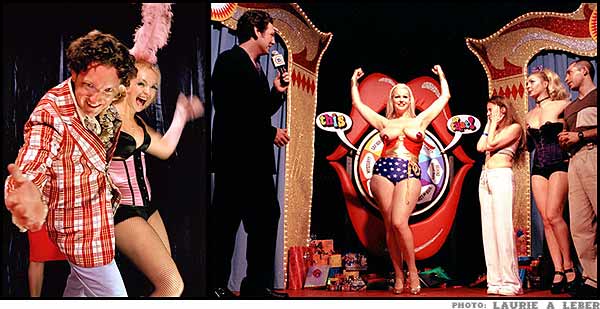

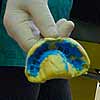

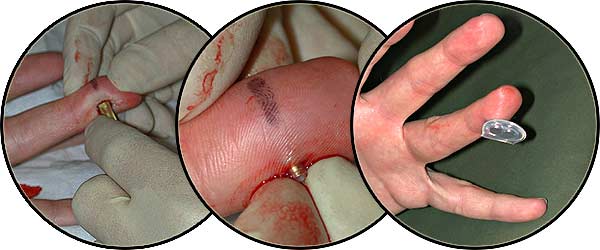

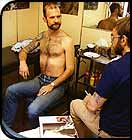

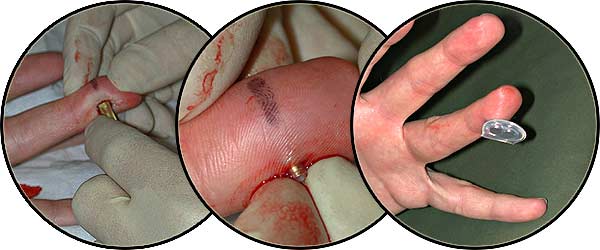

Photos of Todd’s implants being inserted by Steve, and showing them responding to a magnet.

Photos courtesy of Steve Haworth and Jesse Jarrell.

A fascinating letter from the client was posted along with it — he’d had a small silicone-coated neodymium magnet implanted, and it turned out to be far, far more than just a party trick!

Sensory Experimentation Somatosensory Extension

Reflections by Todd M Huffman [excerpt]

I am now able to perceive magnetic fields in ways not naturally possible. The sensation is different than holding a magnet, as the neurons are stimulated with a higher resolution. With the implant I can detect subtle changes in polarity and strength that I cannot when equipped with a magnet in the conventional manner. Yet the most significant observations have come from another property of implants, their relative permanence to exogenous artifacts. Being able to perceive magnetic fields has expanded my conscious perception of magnetic fields ‘in the wild’.

In one sensory incident, I was walking out of the library, and I sensed the inductive anti-theft device. I have walked in and out of dozens of libraries hundreds of times, and never once have I thought about the magnetic fields passed through me to prevent me from stealing a book. I have been intellectually aware of the mechanism, but never paid attention until now. Another time I opened a can of cat food for my girlfriend’s pets, and I sensed the electric motor running. My hand was about six inches away from the electric can opener, and I was able to sense where the motor was inside of the assembly. Again it brought my attention to a magnetic source that I understood intellectually, but would have otherwise been unaware of. I feel I am one step closer to fully grokking the reality I inhabit.

The experience of my implant is not nearly as rich as my visual or auditory sensation, but nevertheless after a week it has dramatically changed the way I think about my daily sensory experience. A small magnet embedded in a finger may seem like a trivial exercise. I find it difficult to explain the significance, somewhat akin to trying to explain to a blind person what it is to see. The problem isn’t defining the technical characteristics of the visual system, but one of trying to convey what conscious perception of certain wave frequencies does to the way a person conceptualizes the world.

In modifying my body I have ever so slightly altered the way I organize the world in my mind. I eagerly await the day in which I can integrate more elaborate senses into myself. With every passing minute I try to see radiant heat, hear radio waves, and think the thoughts of those that pass by. And by better understanding what I cannot feel, I can fully appreciate what I have now.

I was floored. This seemed to me to be one of the biggest steps body modification has taken. The notion of enhancing sensation is nothing new to anyone with genital modifications, but the idea of adding something fundamentally new to the function of the body is a radical concept that only a few people have done meaningful experiments in. I had to interview Todd about his experiences, and he was happy to help us out.

BME: Tell us a bit about yourself… Where are you from?

TODD: I grew up in Los Angeles and a small town, Teutopolis, in southern Illinois. When I was growing up my main interests were in emergency medicine. I started college studying nursing, with plans to continue on to medical school. While in high school I got my certification as a Nurses Assistant, and completed a course to be an EMT. These experiences are relevant because I was very thorough in my research on body modification, the effects of magnetic fields on tissues, implant construction, and the specific procedural skill of Steve Haworth (the implant artist who worked with me on the project).

I worked as a nurse’s assistant in the St. Louis University Hospital Neurology unit, where I developed my interest in neuroscience — and my aversion to medicine. I don’t dislike the medical profession per se; I just prefer an occupation with more freedom. I moved back to California to attend California State University at Long Beach and studied neuroscience. After graduation I took a job with the Alcor Life Extension Foundation (alcor.org), and will be working there for two years until I start graduate school.

One important aspect of my life is transhumanism. I have been identifying myself as a transhumanist since the age of thirteen, when I discovered the website of the Extropy Institute and the philosophical writings of Max More (maxmore.com) and Nick Bostrom (nickbostrom.com), among others. The transhumanist philosophy has provided a useful framework for me to build ideas and concepts upon, such as the concept and practice of attempting to extend my sensory experience.

BME: Did you have other modifications before this particular “upgrade”?

TODD: Before this my body modifications have been limited to piercing, both cosmetic and play. Our society has perfected the art of pain avoidance and disassociation from our bodies. Piercing and other body modifications bring the mind back to the body and increase a person’s awareness of their physical self. For such a materialistic society, America has lost touch with their physical self.

BME: So this the first “functional” modification you’ve gotten?

TODD: Yes. The magnetic implant is probably the crudest form of functional implant. It pales in comparison to much more complex implants that interface directly with neurons, such as cochlear implants. As a point of clarification, my magnetic implants are more effective as a conceptual tool, rather than for real world use. The plans were more for the exploration of sensory experience than for a specific task that would increase my functional abilities.

BME: For those that aren’t familiar, could you tell us a bit about cochlear implants?

TODD: Cochlear implants are a medical device that bypasses damaged structures in the inner ear and directly stimulates the auditory nerve, allowing some deaf individuals to learn to hear and interpret sounds and speech.

My involvement with cochlear implant research was analyzing the electrophysiological brainstem response of implant patients with a particular disease, auditory neuropathy. I did this for a semester as an independent project, and the bulk of my time was spent in front of a computer working with numbers. However I did on several occasions assist in the data collection procedures, and talked with people who had cochlear implants. I was fascinated with the possibility of gaining a sense with technology that was forbidden by nature.

Fortunately I have all the senses normally accorded to a human being. Current medical devices are not capable of giving me additional sensory experiences. Steve Haworth, Jesse Jarrell, and I were discussing various implants, and Jesse mentioned a friend of his who got a steel sliver in his finger and could sense speaker magnets. Jesse and I had previously discussed implanting magnets, and the idea was born. I was highly motivated to get the implant because of the possibility to explore a new sensory modality.

BME: How did you refine the idea into something functional?

TODD: I spent several months researching magnetic implants. I was concerned the magnet would attract iron particles from degraded red blood cells and cause irritation in the surrounding tissue. A significant amount of research has been done by the medical field and my concerns were alleviated. After that Jesse and I ordered a batch of neodymium magnets from a supplier and played with size combinations. After determining the sizes and shapes of the desired implants, Jesse made several prototypes. Jesse and I tested the implants to make sure the coatings were sufficient, and Jesse made the implant that was actually implanted.

BME: How was the healing?

TODD: Healing was great. I had feeling back by the next morning, and full sensitivity back in a week. The scarring is minimal, and is not noticeable unless you are looking for it. The next day my finger felt like I had slammed it in a car door, but that is expected. There has been no prolonged discomfort.

BME: Is the implant visible?

TODD: Not visible at all. If someone palpates my fingertip and knows exactly where the implant is they can feel it. A friend of mine couldn’t find it until I pointed out the location.

The goal was to have it as unobtrusive and natural as possible. The reason for this was not to hide the implant from other people, but to hide it from myself. I want the sensation to seem as naturally endogenous as possible. I want the sensation to integrate as much as possible with the rest of my sensory experience.

BME: How does it feel to you in the absence of a magnetic field?

TODD: I feel nothing, just like any finger experiencing normal conditions. Humans ignore the majority of sensory experience, a necessity given the barrage of information thrown at us by reality.

BME: And when you move into a magnetic field, what does it feel like?

TODD: There are two distinct feelings I get from fields. For a static field, like a bar magnet, it feels like a smooth pressure. Imagine running your hand slowly through lukewarm water, and brushing your finger across the top of a large invisible marshmallow. That is the closest description I can give. Oscillating fields, such as electric motors, security devices, transformers, et cetera, vibrate the magnet. This sensation is much more sensitive and noticeable.

BME: How sensitive is? Can you tell the direction of a field?

TODD: The implant is rather sensitive. I can tell the polarity of a bar magnet from several inches away. So far the furthest I have felt an oscillating field has been about two and a half or three feet. That was the security system in a video store, which uses magnetic induction.

BME: You can “feel” for anti-theft devices? You’re getting all the super-villains excited!

TODD: All you would-be criminals don’t get your hopes up. I can only detect the active components of anti theft devices — those stands by the exits of stores. The actual component inside the item does not generate its own field. I just get a buzzing feeling when going through security systems.

BME: How “fine” a sense is it? Does it feel like a sense like sight or hearing, or more like a “sixth sense” in that it’s more of a “gut” or instinctual sense?

TODD: The feeling is rather fine. I can detect different frequencies in the magnetic fields. I haven’t done experiments yet to determine the sensitivity range, but I will in the near future. The sensation is rather intuitive, and exploring a magnetic field is not unlike trying to identify an object with your eyes closed.

BME: Does it feel like a sense in and of itself, or is it more of an “interface” between a sensory device and your nervous system?

TODD: The implant does not feel like an ‘alien’ artifact, it is much closer to a natural sense. When the sense is not active I don’t feel the implant and don’t really think about it. If the sensation were coming from an external source, it would feel much more like an interface object rather than an actual sensory experience.

BME: Will you expand this to your other fingers as well, or do you feel that wouldn’t add to the experience? I’m having visions of mechanics that will be able to run their fingers over an engine and diagnose problems because of imperfections in the magnetic fields.

TODD: I don’t think this type of implant will ultimately prove to be useful. However, my intentions were exploratory, and the case may be that this type of implant has many more uses. There are a few ideas I have that may involve adding more implants.

BME: Do you have plans to add other senses as well?

TODD: I would like to add as many senses as I possibly can. One area I am considering is using the implant, and others as needed, as a form of haptic feedback. Computer interaction is developing at a snail’s pace, whereas almost every other index of computer development is racing at exponential rates. Our main form of computer input — the keyboard — is over a hundred years old. Even the mouse is over thirty years old. Monitor technologies have progressed very slowly, and are fundamentally the same as they have always been. I don’t expect everyone to go out and get magnets implanted in their fingers, but as a society we need to think outside the box and devise new ways to interact with computers.

BME: Are you finding that it is having a functional impact on the way you perceive and interact with the world?

TODD: The implant has changed my perception of the world around me in a small but significant way. Information is constantly flowing around us, and we remain blissfully unaware of most of it. Having a tiny bit of that data stream pulled into your conscious awareness is a shocking experience. Functionally I have changed very little, but I am now more aware of what it is I don’t feel. There is an untold amount of information flowing around us that we don’t experience; my implant makes me think about this more.

BME: Did you do any psychological (or other) preparatory work before the implant?

TODD: Before the actual implant there were several months of planning and hypothesizing, and thus I was well prepared for the procedure and the implant. There were unexpected sensations, and some sensations were missing I thought would be noticeable. I can’t say I would recommend any particular preparation, as a person willing to put implants into themselves should be able to handle small changes in their sensory paradigm.

BME: Can I ask a little about your research work for Alcor, and how that relates to this implant?

TODD: Alcor and the body modification community have a lot in common. The classic members of both communities are individualists with strong personal identities. Neither group is afraid to push the envelope of what is accepted by the populace around them. Transhumanism is a philosophy that does not encompass all members of both communities, but I have noticed a significant level of overlap. I think this is the case because transhumanism as a philosophy encourages exploring boundaries and transforming yourself.

Alcor employs me as a Research Associate, and I am part of the research and development team. My main task is to research and evaluate methods of preserving and storing neural tissue. My research at Alcor is unique because no other organization is concerned with preserving tissue in the manner we are. The research is significant not only to cryonics, but a lot of our research has applications in other areas, such as organ transplantation and storage.

All of this ties together because ultimately I am interested in pushing the boundaries. Pushing boundaries is, in my opinion, the quintessential characteristic of humankind. An a priori acceptance of the status quo on the part of our ancestors would leave you and I as naked apes hiding in the trees, or more likely, extinct. Both cryonics and body modification are controversial and exciting, just like writing or forging metal or flying.

BME: How did you meet Steve and Jesse, and what made you decide to work with them, rather than working with a doctor or more traditional medical team?

TODD: Jesse I met at a Los Angeles Futurists meeting, where we were attending a talk by Syd Mead. Later I met Steve through Isa Gordan, an artist in the Phoenix area.

As Steve and Jesse became friends with me, we discussed body modification and my medical background, and Steve allowed me to observe several procedures. Steve’s protocols for infection control and cross contamination avoidance are on par with a hospital setting, and I felt confident in his technical abilities. In addition, there is a high level of artistic vision in implant work, which I do not think can be met by conventional medicine.

BME: So there were advantages to doing it without the constraints of the medical industry?

TODD: Steve and Jesse provide the professionalism and concern for safety provided by traditional medicine while incorporating artistic vision and skill. Doctors, even cosmetic surgeons, would have likely shied away from doing this type of implant work. The fear of the unknown would dissuade most doctors from assisting me in the project.

BME: Any advice for people considering adding this sense or others?

TODD: Exploring sensory experience is a fundamental quality of human beings, be it through implants or pharmaceuticals or technology. Before any experimentation you are obligated to yourself to perform thorough research into the subject, as it is very easy to harm yourself. Personal responsibility is even more important than experimentation.

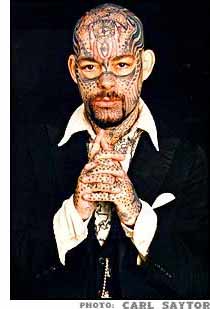

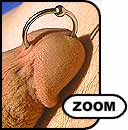

Jesse’s own magnetic implants, for utility rather than sensation.

Photos courtesy of Steve Haworth and Jesse Jarrell.

Thank you to Todd for taking the time out to talk to us. If you’d like to contact him, you can do so via email at odd1 at onebox.com. If you are looking to have this procedure or one like it done yourself, contact Steve Haworth via stevehaworth.com.

Shannon Larratt

BMEzine.com