(Editor’s note: This article was first published in The Point, the publication of the Association of Professional Piercers. Since part of BME’s mandate is to create as comprehensive and well rounded an archive of body modification as possible, we feel these are important additions.

Paul King, the article’s author, has given BME permission to publish a series of articles he wrote for The Point that explore the anthropological history behind many modern piercings. This is another in that series.)

In Sulawesi it was called Kambi or Kambiong; in the Philippines, Tugbuk. In southern Borneo it was called Kaleng and, while the Kenyah called it Aja, the Kayan called it Uttang or Oettang. A few anthropologists made the Iban’s name for it the most famous: Palang, or ampallang. An Indian scholar gives a description of it and calls it apadravya. First of all, the reader will come to know that what we have all called the ampallang and the apadravya piercings are, historically, one and the same. This article will cover origin, practices and mythology around this very extreme and ancient piercing.

As to the exact origin of this piercing, nobody knows. Scholars have devoted their careers to dissecting trade patterns, in particular in South and South East Asia. The complexities of trade influence over time can most simply be described as the overlapping of cultures, like waves crossing from different directions. Based on the knowledge that all known occurrences of this custom are recorded on the same trade routes and the intense nature of piercing and healing the glans of the penis, one can safely deduce that this piercing custom did not spontaneously originate in various locations, but was shared.

The only known reference of the apadravya is the sixth century Kama Sutra. I know of no other mention or art depictions of the piercing in India. If the practice survived until substantial European contact, in the seventeenth century, then surely there would have been some recording. One can only speculate that this piercing was probably neither widespread nor lasting in the Indian culture.

According to Vatsyayana, the author of the Kama Sutra, apadravyas are any one of a number of devices which a man

puts on or around the lingam (penis) to supplement its length or its thickness, so as to fit into the yoni (vagina). The people of the southern countries think that true sexual pleasure can not be obtained without perforating the lingam, and they therefore cause it to be pierced…now when a young man perforates his lingam he should pierce it with a sharp instrument, and then stand in water as long as blood continues to flow. At night he should engage in sexual intercourse, even with vigor, so as to clean the hole. After this he should continue to wash the hole with decoctions and increase the size by putting into it small pieces of cane… and thus gradually enlarging it.

There should be some debate on the definition of the term “southern countries” used in the Kama Sutra, It could mean Southern India or it could mean SE Asia. If it means SE Asia, again, this would argue that the origins of the piercing are probably not in India.

The first known depiction is on a bronze dog from SE Asia, fourth century. The earliest record in European literature of the piercing on a man is from 1588. The explorer, Cavendish, is said to have been to the island of Capul, Philippines. “Every man hath a nayle (nail) of Tynne (Tin) thrust quite through the head of his privie part (glans of his penis)…” 1

Though the Indian culture was extremely prolific, there is another good argument against Indian origins: Statuary predating Hindu influence in Bali depict possible penile piercings. One anthropologist has cited the visual influence of certain indigenous rodents and the rhinoceros on the island of Borneo (that naturally have barbed penises) as the original inspiration for the piercing.2

The only traditional practice of this piercing still known to exist is on Borneo, with the Kayan people believed to be the oldest practitioners of the Palang; all current tribes practicing the palang give credit to the Kayan. This is interesting, considering they are inland and thought by anthropologists to be the most isolated and oldest inhabitants. Current history dates the palang to other tribes only about 100 years.3

Just as interesting as the mysterious origins are the variations of materials, practice and mythology around this extreme piercing.

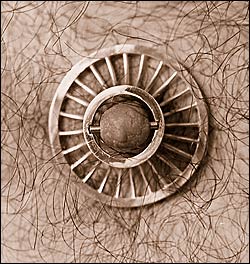

Other than the mention in the Kama Sutra, the oldest accounts of this piercing come from the Philippines. Popular in the region was a device called Sakra, which is believed to be a derivative of the Indian Sanskrit word chakra: a center of force or energy. The apparatus could be a round wheel with projecting points (like a spur held in place by a pin), stars, rings, fine twisted wire, pig bristles, bamboo shavings, seeds, horn, coral, agate, hornbill ivory, beads, broken glass and, in one case, an object that looked like a snake head. Quills, as well, were used as nonfunctional retainers. The early explanations from the Codex say the women insisted upon the piercings to discourage the men from sodomy. The Spanish quickly set about eradicating the behavior, referred to as “a custom invented by the devil.”4

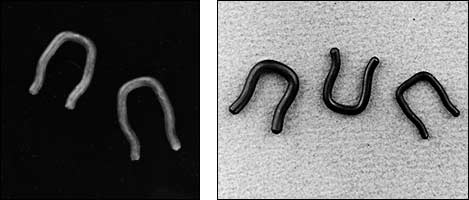

Certainly the greatest volume of documentation for this piercing, however, is from the Iban in Borneo, who would sometimes tattoo a rosette (or, occasionally, a fishhook) to show they had a palang. Palang in Iban means “cross” or “cross bar,” and, in the region, the Pins would be made of gold or brass. Often, a sleeve insert to reduce friction (a “bushing”) was put in place so the pin could be removed as desired,5 with up to three palangs sometimes worn at a time.6 The Iban also refer to the ampallang as “burah palang” or “tanduh duri,” which translates to “spout thorn” or “point.” The ends of the pin could have been smooth, or may have been “little pins, coins, discs, brushes, rings/rowels.”7

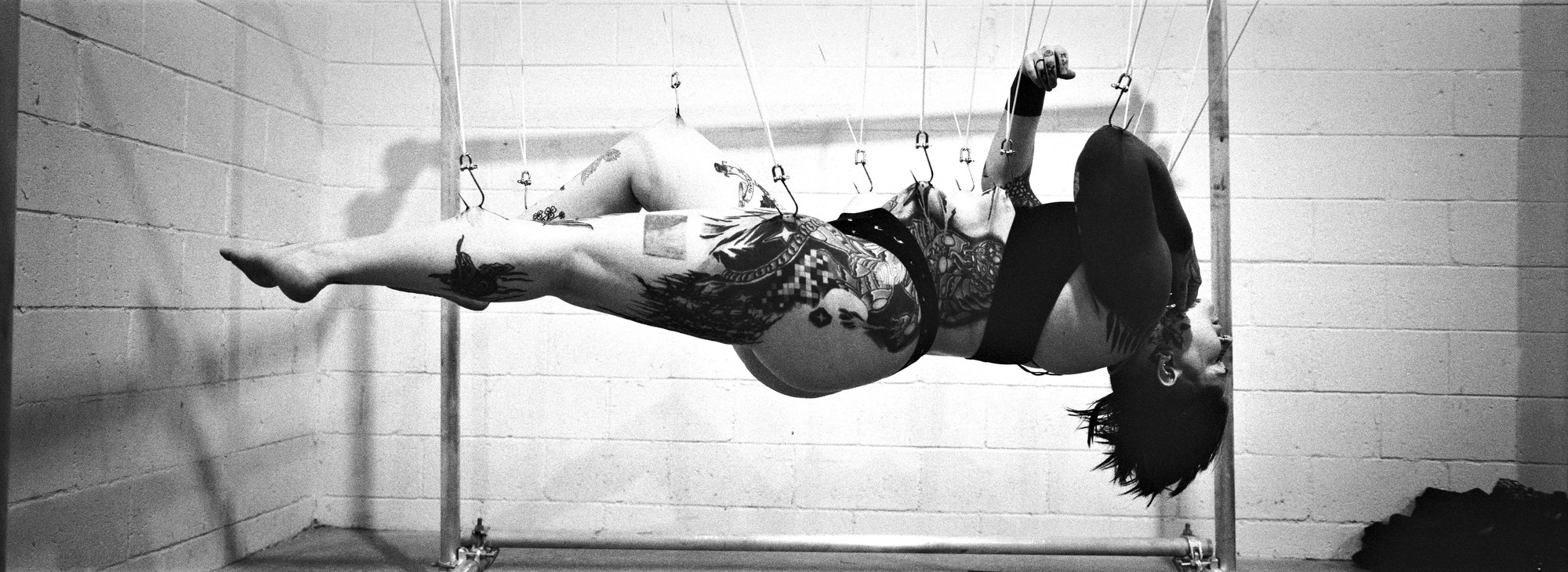

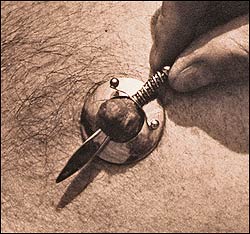

On Borneo and Sulawesi, a splint is used to hold the penis for the actual piercing procedure. It varies in length from several inches to a foot, approximately a one-and-a-half inches thick with a hole in both sides.8 The slats are placed on either side of the penis and then tightly secured, flattening out the penis. After sufficient time has passed for the lack of blood and cold water to decrease sensation, the penis is pierced9 – sometimes, a pigeon’s feather anointed with oil would be inserted and taken out each day. The piercing takes about one month to heal.

There are many myths of origin for this piercing. The Kayan say a woman complained of a man’s penis size, saying it was no better than a rolled leaf used to give herself satisfaction, and the insulted male ran off to the woods and pierced himself. The Kelabit say a visiting Kayan warrior used his piercing on a woman causing her death, but she was so satisfied the Kelabit continued the practice.10 Another story goes11:

“The lady had various ways of indicating the size of the ampallang desired. She might hide in her husbands plate of rice a betel leaf rolled about a cigarette, or with the fingers of her right hand placed between her teeth she will five the measure of the one she aspires. The Dayak women have a right to insist upon the ampallang and if the man does not consent they may seek separation. They say that the embrace without this contrivance is plain rice; with it is rice with salt.”

In the mid 1970s, Doug Malloy labeled the vertical piercing of the glans an “apadravya” and a horizontal piercing “ampallang.” Doug passed this folklore onto Jim Ward, founder of Gauntlet and editor of Piercing Fans International, Quarterly.12 For posterity, it’s important that the piercing community knows the historical origins, however, continuing the practice of differentiating the same piercing as two, honors our own western traditions.

________________

1 Male Infibulation by John Dingwall

2 Tom Harrison is an anthropologist from the 1950s and 60s. He wrote several articles, a book and collected artifacts on the Palang for the Sarawak Museum, Kuching, Malaysia. This author was able to go there and obtain photocopies of his work.

3 Tom Harrison

4 The Penis Inserts of Southeast Asia Donald E. Brown, James W. Edwards, and Ruth P. Moore

5 The Sexual Relations of Mankind (SRM, per researcher Von Graffin) by Montegazza

6 A Stroll through Borneo by James Barclay

7 Tom Harrison

8 Tom Harrison

9 SRM states they will sometimes leave the device on for eight to ten days. (!) An Iban personally told this author, “2-3 hours.”

10 Tom Harrison

11 SRM

12 Per telephone conversation with Jim Ward, August 3, 2002.

My usual disclaimer: I am not an anthropologist. From time to time, there will be errors. Please be understanding and forth coming if you have any information you would like to share.

Please consider buying a membership to BME so we can continue bringing you articles like this one.

![]()