What Sean Dowdell misses most about the old days — and as of April, his “old days” will go back 15 years — is having his Club Tattoo crew be a tightly knit family that would spend damn-near every waking second together. Back then, it was him and four others, working out of Dowdell’s original Club Tattoo shop in Tempe, Arizona, that he opened with his friend, business partner and then-bandmate, Chester Bennington, now of Linkin Park. Those were days when there were eight tattoo and piercing shops in Arizona, total, as opposed to the 140 or so that one can now find in Phoenix alone. Dowdell and his crew would go out every night, hang out on their days off — closer than blood in some ways, he says. That’s what he misses.

But that isn’t to say he resents his current station in life. Over the last five years, Dowdell has opened up three more Club Tattoo locations in Arizona, expanding that family to 54 employees. Not as tight as the days when one might have found the eventual lead singer of Linkin Park painting the walls and laying tile, perhaps, but Dowdell stresses the importance of cohesion in the face of expansion: A person, any person, should be able to walk into any Club Tattoo and have it feel familiar, he says, and that includes employees.

And what better place to put to the test a mandate of cohesiveness than Las Vegas? On December 1, 2008, Dowdell oversaw a crew begin construction on the newest addition to Club Tattoo: a 3,300-square-foot shop opening up March 1, 2009, on the Miracle Mile in the Planet Hollywood casino, with a staff of at least 14 tattooists and piercers, plus clothing (Club Tattoo has its own clothing brand and recently launched a menswear line called Ve’cel) and high-end body jewelry. But don’t call it a tattoo parlor, Dowdell says: “I’m opening up a lifestyle store.” It’s partially because of this that he doesn’t see himself in competition with Mario Barth at Starlight or Carey Hart at Hart and Huntington, two other prominent casino-based shops in the city.

“Carey is a really good friend of mine,” Dowdell says, dismayed that Hart gets a bad rap in the industry for not being a tattoo artist, “and I want to keep it that way. I’m not looking at it like, ‘Oh, those guys tattoo also, so I have to hate them.’ I’ve never agreed with that behavior. It’s not a positive quality to have.” There’s also the fact that each casino is like an entity unto itself, and with 60,000 to 80,000 people walking in front of your store a day, one is less concerned with a so-called “competitor” down the street. Hell, with crowds like that, it’s almost like being on stage, and for a guy who used to think he’d be a rock star first and run a piercing shop on the side, it’s perhaps fitting that Dowdell would end up on the Vegas strip — at Planet Hollywood, no less.

In 1992, a few years before Club Tattoo first opened its doors, Dowdell played drums for Grey Daze, an alternative rock band fronted by Bennington. They weren’t unsuccessful, managing to score a handful of record deals over six or seven years, putting out three albums, and touring with the likes of Seven Mary Three, Candlebox and Suicidal Tendencies. “It wasn’t a little local band,” Dowdell insists. “We were playing in front 1,500 to 2,000 people every show, at least.” And when the pair started Club Tattoo in 1994, it was Grey Daze that helped put them on the map. Every show was an opportunity to promote the fledgling shop, an advantage that few young businesses have, and by the time the band had run its course in the late ’90s, Club Tattoo was a legitimate success. Plus, with Grey Daze having some cachet, the stage was set for Linkin Park, as well. “We still had our attorneys and everything,” Dowdell says, “and they were still excited about what we were doing, so they placed Chester with a few guys from L.A. and plugged in the machine that was there.” For Dowdell, it was actually a relief to get off the road. “I hate touring,” he says plainly. “It sucks. Seventeen hours of boredom, a couple hours of soundchecks and more boredom, an hour of fun, and then you go to sleep and do it again. There’s just not enough going on on the road.”

Funny, then, that Dowdell found himself touring another circuit over the past two years — and loving it. Having gotten high-profile magazine recognition for some large-scale microdermal projects he’d been doing, he started getting calls from tattoo convention promoters to teach a microdermal seminar. He’d never considered teaching, but after consulting with his friend Trevor Thomas of Urban Art Tattoo and Piercing in Mesa, Arizona, the two decided to give it a shot. Their first crack at it went well, and before long they were being courted by dozens of conventions across the country, drawing an average of 50 attendees per appearance, and typically garnering overwhelmingly positive feedback.

“I wanted to have two different aspects of doing dermals,” Dowdell says of his reasoning for wanting to include Thomas: Dowdell uses the dermal punch method, while Thomas works with an 11-gauge needle. “It’s kinda cool, because when we’re teaching — I wouldn’t say we argue, but we debate a little bit on techniques and why we think things work. It’s a fun situation.” After a while, however, requests for classes started coming from places too remote to justify the travel time and expenses. “I had a few piercers who wanted me to go to Calgary to teach, and I thought, ‘Well, that’s gonna take four days of traveling to get there,’ and it just wasn’t financially worth it — as much as I like to teach people.”

It wasn’t finances that put an end to the seminars, however. After a class over the summer — Dowdell forgets where, but, “Probably Atlanta or Philly,” he says — Dowdell jacked up his back during a game of pickup basketball, herniating two disks and relegating himself to couch duty; between the injury and the subsequent surgery and rehab, he was out of commission for four months. His status started to improve towards the beginning of December, but a relapse sent him back to the hospital for a week. Traveling had been out of the question entirely, so it was lucky that he’d already been working with Vanessa Nornberg, the president of the jewelry wholesaler Metal Mafia, on putting out the course as a DVD and booklet. For Dowdell, given the popularity of the seminars, putting out the DVD was a no-brainer, though the catch was that Nornberg would only sell it to shops with which she had a good rapport.

It wasn’t an accident that it was Metal Mafia to put out the DVD. A year and a half earlier, Dowdell had teamed with them to design and manufacture a new piece of microdermal jewelry. He’d had experience in the field: Around the time he opened up his first Club Tattoo shop, he also began making and selling jewelry under the banner of Fetish Body Jewelry, a company he sold three years later. “I definitely have a wide background in [jewelry making],” he says. “The alloys, what’s in the compounds, the metallurgy involved and how to cut, how to anodize, all that stuff.” So when he ran into Nornberg at a trade show a couple years back and told her the microdermals she was promoting at the time were terrible, it was at least partially out of professional courtesy. “They had this other dermal anchor they were pushing from another piercer named Ben Trigg,” he says, “and I’m sure he liked the stuff, but I hated it. I thought it was awful. And when they asked if I would take on their jewelry line at the shops, I said, ‘No,’ and told them why. I was not nice about it.”

Five months later, however, Dowdell got a call from Nornberg; what he’d said had resonated, and she wanted his help. “At the time,” says Dowdell, “I was not a fan of Metal Mafia, on account of the sub-par jewelry they were selling,” but after meeting with Nornberg, he was convinced that the company was truly dedicated to improving their product. He’d been speaking with other jewelry manufacturers beforehand, and was unimpressed with their philosophies and methodologies. “Usually, you’re dealing with jewelry companies who just don’t want to spend the money to make jewelry the right way — and that includes some of the bigger, more well known companies,” he says. “And I kept talking to these companies, saying, ‘Well, this would be better if …’ and they’d say, ‘Yeah, but it costs too much money, we’re not gonna do it.’

“Well, you’re not a piercer, and you have a piercer who knows what he’s talking about telling you that this should be better, and you don’t care because of money. That sucked.”

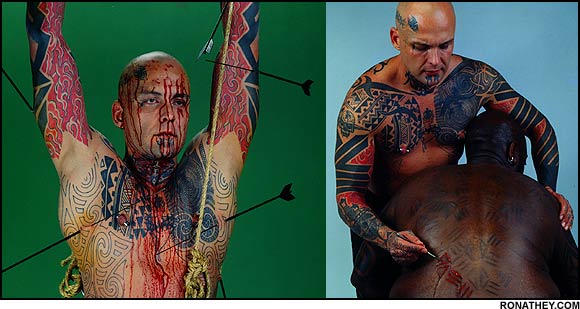

|

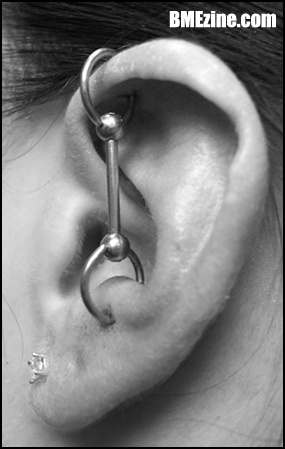

| “Permanent” corset with microdermals by Sean Dowdell. |

But Metal Mafia, he found, was different, almost repentant, and when he took that call, Nornberg essentially told him that she knew they weren’t an elite jewelry company, but she was prepared to spend the money to make sure they became one. “It was a very bold way to approach it,” Dowdell says, who hopes the trend of jewelry companies consulting with piercers when designing jewelry continues. “They can’t just produce poor quality jewelry and put it out there and expect to be respected.”

Dowdell is big on respect. At this point, he feels like he’s earned it, but being as successful as he is, he’s used to being trashed publicly. “With four large shops here in Arizona,” he says, “some of the smaller shops just think we suck because we’re popular. Well, OK. That’s just the way it goes in business, I guess — once you start doing well, you’re gonna have haters.”

But does he take it personally?

“If it’s personal, I do!” He laughs. “If it’s somebody running their mouth and they’ve never been in the stores, then no. But my shops have set the standard in Arizona, and that’s just the truth of it, whether they like it or not.”

|

It’s bravado, to be sure, but it’s well-earned — and probably a necessity with Club Tattoo’s upcoming Vegas expansion, a project that itself is nearly five years in the making, that began with Dowdell being approached by the Hard Rock about opening up a shop on the grounds.

“We came down to the finishing touches on the lease,” he says, “and then they jacked us pretty good. One of the guys ended up taking a bribe from another tattoo shop that got wind of the deal, and we ended up getting pushed aside so they could get those guys in there, even though we’d worked for months with them.” But of course, nothing in Vegas is ever that simple. “They have to do background checks in Vegas, and it turned out that one of the guys had a sexual assault on his record, so they couldn’t give them the lease.” The Hard Rock came back to Dowdell, who told them to go screw — he was being courted by another casino, called The Cosmopolitan.

“It was right around the time that Hart and Huntington opened up inside The Palms,” he says, “so we agreed to go with The Cosmo, which was supposed to open last year. Well, they went into bankruptcy after we’d already had our lease in place with them, and at the time, we’d already been delayed for a full year. We were tired of waiting.”

Luckily, Planet Hollywood had been keeping tabs on the situation, and once The Cosmo deal fizzled out, they made their move, and Dowdell has been thrilled with the results thus far. Planet Hollywood was one of only a few casinos with positive growth in 2008, Dowdell says, and its demographic — 18-to-35-year-olds — fit right in with Club Tattoo.

As the opening of the Planet Hollywood shop approaches, Dowdell’s days are only getting fuller. He still pierces (by appointment only), and typically visits at least two of his Arizona shops a day to check in with his artists and piercers, to make sure the jewelry cases are well organized and that all buying is up to date, and to deal with any complaints from customers. “Generally, there aren’t any,” he says, “but I like to deal with those first thing in the morning.” His afternoons usually involve a couple of meetings, plus, at the moment, speaking with the Vegas construction crew for at least an hour, and he tries to be home by about 6 p.m. to spend time with his two sons, aged 13 and eight. His staff may not be the small and symbiotic family it was 15 years ago, but having a family of his own makes those sorts of changes easier to deal with.

He prefers where he’s at now, the slow and steady shift from managing an independent shop to overseeing a burgeoning chain delivering plenty of satisfaction. He balks at the idea, however, that it was a natural progression. “I saw an opportunity,” he says. “You have to be prepared when an opportunity presents itself and make the best of it. Some people do and some people don’t.”

|

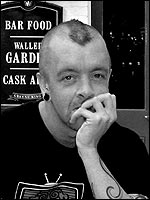

| Club Tattoo partners, left to right: Sean Dowdell, Chester Bennington, Sean’s wife Thora Dowdell. |

All photos courtesy of Sean Dowdell. Visit Club Tattoo online at ClubTattoo.com.

Please consider buying a membership to BME so we can continue bringing you articles like this one.