Rape is an act of violence that, in practice, takes something beautiful and turns it into something ugly. We are familiar with acts of rape in prison, of our women, and of our children.

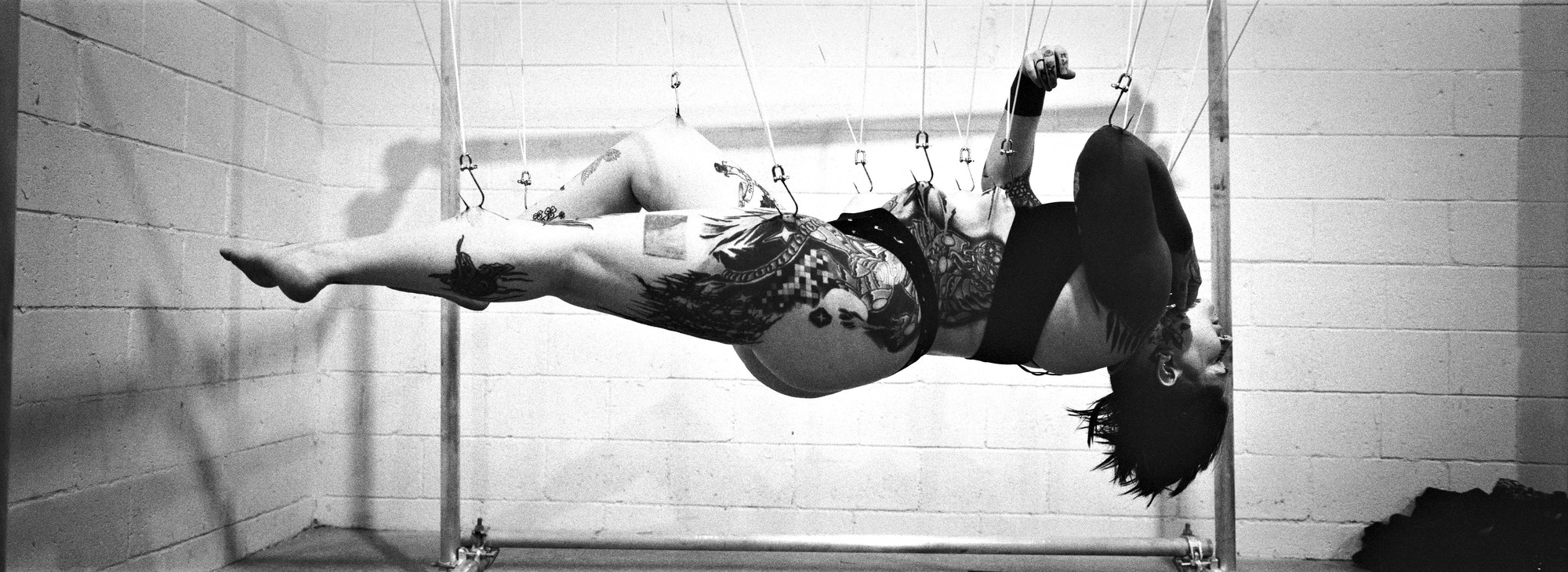

Rape by tattoo is not a new concept; most of us are familiar with the numbers etched onto the arms of concentration camp victims. (Survivors’ stories are in the news all the time, but they’re generally not part of the BME Newsfeed. We did, however, log David Blaine honoring Primo Levi by getting Mr. Levi’s number, 174517, as a permanent tribute.) I first read about this cruel practice in the noir thrilled Flood. In a very moving scene, the beautiful Flood shows the scar from when she used gasoline to burn off the tattoo bikers put onto her thigh. Later, I learned more about it in the rec.arts.bodyart FAQ. What makes this a particularly brutal crime is that the survivors’ scars are visible as well as emotional.

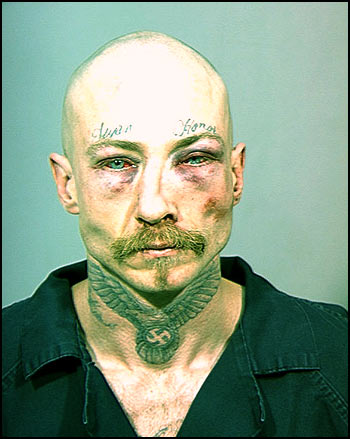

This crime has been prelavent in the news in recent months. Dr. Gregory Roche removed a vulgar tattoo from the face of a New York teenager after some former friends and he got into a fight over a girl. A gay inmate in Texas has been granted permission to sue the state; in addition to sexual abuse, the inmate’s face had been forcibly tattooed.

Recently, the tables were turned in the UK. Jackie Clarke lured her alleged rapist to her home, drugged him, and then used a pin and ink to tattoo “Rapist” onto his penis. While fellow victims around the world may cheer her on, the judge hearing her case says that her actions “amount to torture.”

A pimp in Illinois tattooed his nickname, “Mr. Cream,” onto the bodies of two teenage girls. In a happier turn of events, justice may be served: he crossed state lines, and the FBI and US Attorney now plan to make an example out of Mr. Cream.