As part of an ongoing investigation into private rituals and public spaces, this article will consider the growing interest in Live Art in which the artists use their own bodies as the site of inquiry. Social taboos such as bloodletting, self-flagellation and body modification will be considered, alongside the objections to this particular practice.Live Art has its history in the performance art practice of the 1970′s. Informed by the work of such artists as the Viennese Aktionists, Coum Transmissions and Chris Burden, the artists who engage in this particular practice choose to use their own bodies, pushing the boundaries of social taboo. Creating more of an interrogation than a dialogue, the spectator is forced into making choices about questions of identity and difference and the nature of mortality.

In order to negotiate these particular practices has proved problematic, as the performances now only exist in a fragmentary way within photographs and videos. Of course, this documentation is not the performance itself. A photograph or video is a snapshot of time and cannot be totally representative. In an age of mass information overload, where we have become de-conditioned to atrocities committed in the name of politics, global terrorism and famine, the ‘news’ documentation played back on radio and television does not tell the real story. We are conditioned to objectify violations of the body and remove ourselves from immersion in such actions and feelings. The curators (journalists and TV news presenters) of this spectacle manipulate our points of view, numbing us to the reality of events happening in distant countries to ‘the other’.

The use of blood within Live Art forces the viewer into re-considering their own bodily vulnerability and to question issues of gender roles. As Live Artists use their own bodies as a site for inquiry, there is an immediacy of similarity between the viewers and viewed, which does not require any academic training to understand. As such, immediate actions onto the body have generated a discourse that reaches beyond the confines of the Fine Art arena. Press interest has created a reputation for these artists that places them as ‘the other’ onto which we can project our own fears about bodily invasion and destruction, where we can directly experience such violent actions by attending a performance, not constructed and removed from reality in the manner television forces us to.

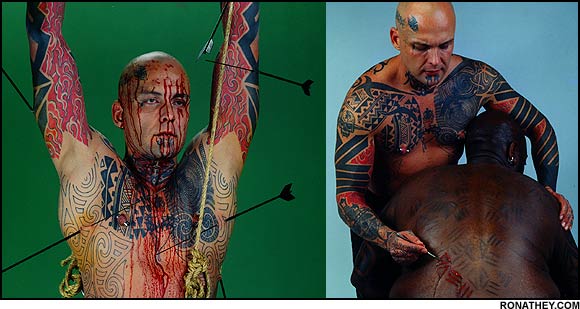

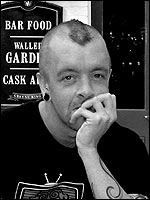

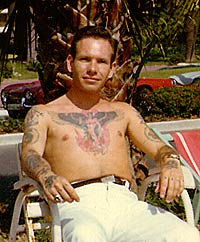

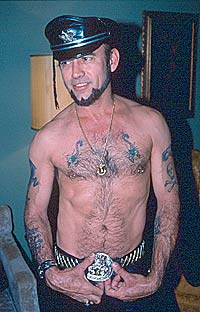

Artists such as Franko B and Ron Athey provoke such a discourse, but one that is fuelled by reputation rather than experience. A sense of control, which could easily lapse into chaos, is the constant concern of such direct actions onto the body. With the disneyfication of difference so prevalent within Western culture, these artists are seeking to re-address the balance and re-affirm their own identities, using taboos such as blood, nakedness and socially sanctioned ‘self-harm’ to explore their own bodies. Traditional Fine Art notions of ‘the space’ and ‘the body’ become ‘this space’ and ‘this body’.

"Like the plague, the theatre is the time of evil, the triumph of dark powers that are nourished by a power even more profound until extinction...The theatre like the plague, is in the image of this carnage and this essential separation. It releases conflicts, disengages powers, liberates possibilities, and if these possibilities and these powers are dark, it is the fault not of the plague nor of the theatre, but of life".

(Exposures, 2002, pg 6)

In “Four Scenes from a Harsh Life” he inserts 30 hypodermic needles into his arm, referencing his time as an intravenous drug user. He then, with the help of his ‘medical’ staff, inserts a crown of ‘thorns’ (hypodermic needles again), enacting Christ’s death. As he collapses on the floor, his assistants cover him with a white shroud and he is carried to the centre of the stage. After a short while he is cleansed with water and is ‘resurrected’.

During “Nurses’ Penance,” he re-creates the institutional terror of a hospital setting, with a patient brutalized by huge drag-queen nurses with sewn-together lips. In another piece he’s writhing naked, on one end of a double-headed dildo. His richest source for material, though, is the church. Most of his pieces have religious names like ‘Martyrs and Saints’ and ‘Deliverance’, along with characters like St. Sebastian, who’s martyred with a literal crown of thorns that causes blood to rain onto his face and the floor. Much of his work is driven by a sense of martyrdom and, arguably, a self-hate instilled on him from childhood.

Athey attracted international attention in 1994, after a Minneapolis performance in which he sliced into the back of a fellow performance artist, placed strips of paper towel over the wounds and then hoisted the bloodied strips of paper towel, via pulley, over the heads of the audience. Though no blood dripped down onto the audience, and though the performer who was cut was HIV negative, Athey’s own HIV positive status led one audience member to claim that the crowd had been spattered with HIV-positive blood.

Within these performances, the spectator is forced into a position of passive voyeurism. The audience act as conduits for this dialogue that is critical to Athey’s performances. Whilst Athey maintains the power, the audience are left helpless as he metamorphoses himself, through methods of live body modification. Although Athey presents himself to us as an artist, he is also allowing us to observe a process of healing and catharsis. Though Athey does not use documentation in a way that is representative (ie he doesn’t exhibit this work in a gallery), videos of his work provide us with a snapshot of the experience of his performances. His use of theatre to present the ‘real’, adds further signifiers to his work. Referencing notions of catholic ritual and linking this to the idea of Christ as drug taker (although by inference) he opens up a discourse on the nature of religion and its use of ritual.

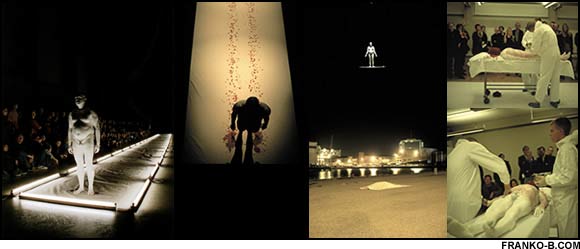

His performances such as ‘I Miss You’, when he walks down a canvas in a room set up like a fashion show, with photographers situated at one end, to heighten the sense of voyeurism, seek to implicate the viewer further. ‘Oh Lover Boy’ sites Franko as an ‘artists model’. To quote from Gray Watsons interview with Franko B,

"Oh Lover Boy is going to be a performance piece where again, the body is presented: it's there on the table. It is there for you to take, in a way, either to draw or to look at...the set-up is going to be almost like a life-drawing class but there is also a clinical side, where it is like you are looking at a body. But it is not passive; it is not a dead body, in a way it's giving life by bleeding. And he's looking at you".

(Gray Watson, 2000)

Franko’s performances reference his childhood being brought up by the Red Cross. Using a diatribe of medical equipment such a syringes, drip stands and wheel chairs, Franko re-enforces notions of healing, but also control, amidst the perceived chaos of his performances. He can only perform three times a year because of the amount of healing that needs to take place after his performances.

Franko’s other work, (which is regularly exhibited, unlike Ron Athey’s documentation) consists of collages and installations. His collage work, references his ‘real’ experiences, and documents his whole life. This again raises issues of vulnerability, as he is leaving nothing to the imagination. Flyers from his performances and pictures of ‘boys I went out with’ (Gray Watson, 2000) mingle with images of religious artefacts and blood stained sheets from his performances.

Issues of power arise here, as the viewer is implicated in the performance by default. Franko appears as helpless and vulnerable, but also has power over his audience. If Franko performed in the street, the context would be different and issues of legality would be raised. This issue of contextualisation also raises issues of safety and notions of control and chaos.

Both Ron Athey and Franko B have ‘medical’ helpers during their performances. They act as signifiers within the performance, to connote to the viewer notions of control and safety. This safety angle is always printed on the flyers, to reassure the viewer. There is a paradox here, as the people that are supposed to ‘help’ during Franko B’s performance, also cut him with a razor during ‘Oh Lover Boy’. The medical helpers are in fact trained body-piercers, with basic anatomy training. As soon as this fact has been established during the performance, these signifiers change.

Both Athey and Franko B as gay men question the nature of masculinity. At their performances, it is the men who recoil against the walls of the venue, normally in foetal positions, returning to maternal signifiers as if about to be castrated. The spilling of blood, whatever the connotation intended by the artist, has the effect of rendering the audience impotent, either to their own bodies or to the performance itself. They cannot help the performers, even though they feel their natural reaction is to do so.

There is also a sense that the performers are acting ‘privately’ and the viewer is intruding into a sacred shamanic ritual. Shamanism is normally associated with women, blood letting during menstruation being an important part of ‘walking with the spirits’. Although, shamans tend to operate outside the confines of accepted social practice, they act as a conduit to ‘other-worldly’ access and are relied upon by the rest of the tribe to maintain a sense of unity. Within the framework of Live Art, the performers provide this access so that the viewers themselves can reach the dark underworld of the shaman. Within Western culture, it appears that men are not supposed to reveal their feelings, let alone share any intimate details about themselves with the outside world. By the direct action onto their bodies and the use of blood, Franko and Athey challenge this notion.

The letting of blood is seen as ‘unclean’. This mythology probably originated in the Old Testament where it is seen that,

"She is to be 'put apart for her uncleanness' for seven days".

(Lev. 18:19)"Any man who lies with her during this time is also unclean for seven days, anyone who touches her is unclean till the evening, and everything that she sitteth upon shall be unclean".

(Lev. 15:19-24)

Throughout the history of art we have encountered images of blood from the earliest cave paintings through centuries of biblical images and through to war films such as Apocalypse Now. It both fascinates us and repulses us. It has come to represent both the sacred and profane. Live Artists use this dichotomy as a way of personal transformation. At the performances there is a sense of sacredness that transcends orthodox religious methods. This could explain why the Christian Church is opposed to such direct actions onto the body. It appals them that something non-religious can actually achieve the same transcendental experience that religion is supposed to offer. In Judaeo-Christian cultures, blood ‘sacrifice’ cannot be culturally sanctioned because of notions of idolatry, where the artist are using their own bodies to ‘redeem’ themselves as opposed to appeals to God.

In his book ‘Violence and the Sacred’, Rene Girards’ theory of sacrifice states,

"The physical metamorphoses of spilt blood can stand for the double nature of violence...Blood serves to illustrate that the same substance can stain or cleanse, contaminate or purify, drive men to fury and murder or appease their anger and restore them to life"

(Girard, 1972)

The process of purification that the artists are trying to achieve can sometimes fail, not providing the audience with the signifier of life that blood performances seek to inform the viewer about. The aforementioned performance by Ron Athey called ‘Martyrs and Saints’ which used supposed HIV blood being heaved across the heads of the audience on a pulley system created an outcry. This could be because the blood was seen as ‘polluted’, making the ‘artist an unacceptable surrogate sacrificial victim for a healthy community’ (Dawn Perlmutter, 2000). In a sense, the signifier contained within the blood changed its meaning and the ritual which was meant to be a demonstration of transcendence through bodily mutilation failed. The distance between the observer and observed was very wide and the artists role as shaman became disjointed, hence the public outcry. The success of such actions is dependent on the audience feeling close to the Live Artists performance.

Jason Oliver

May 2003

References

- Girard, R (1972). Violence and the Sacred. trans. Patrick Gregory. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Perlmutter, D. (2000). The Sacrificial Aesthetic: Blood Rituals from Art to Murder.

- Revised English Bible. (1989). Bath Press: Avon.

- V, Manuel, Keidan,L and Athey, R. (2002). Exposures. Black Dog Publishing: London.

- Watson, G. (2000). interview with Franko B:1st May 2003.

Bibliography

- Danto, Arthur C (1986). The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art. Columbia University Press: New York.

- Eliade, M (1987). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Macmillan Publishing Co: New York.

- Stuart, H (1997). Representation, Cultural Represenations and Signifying Practices. Bath Press Colourbooks: Glasgow.

- Keidan, L, Morgan, S and Sinclair, S. (1998). Franko B. Black Dog Publishing: London.

- V, Manuel, Watson, G and Wilson, S. (2001). Franko B – Oh Lover Boy. Black Dog Publishing: London.

- V,Vale and Juno, A. (1989). Modern Primitives, An Investigation of Contemporary Adornment and Ritual: Re/Search Publications: San Francisco, CA.

- Wollheim, R. (1980). Art And Its Objects. University Press: Cambridge.

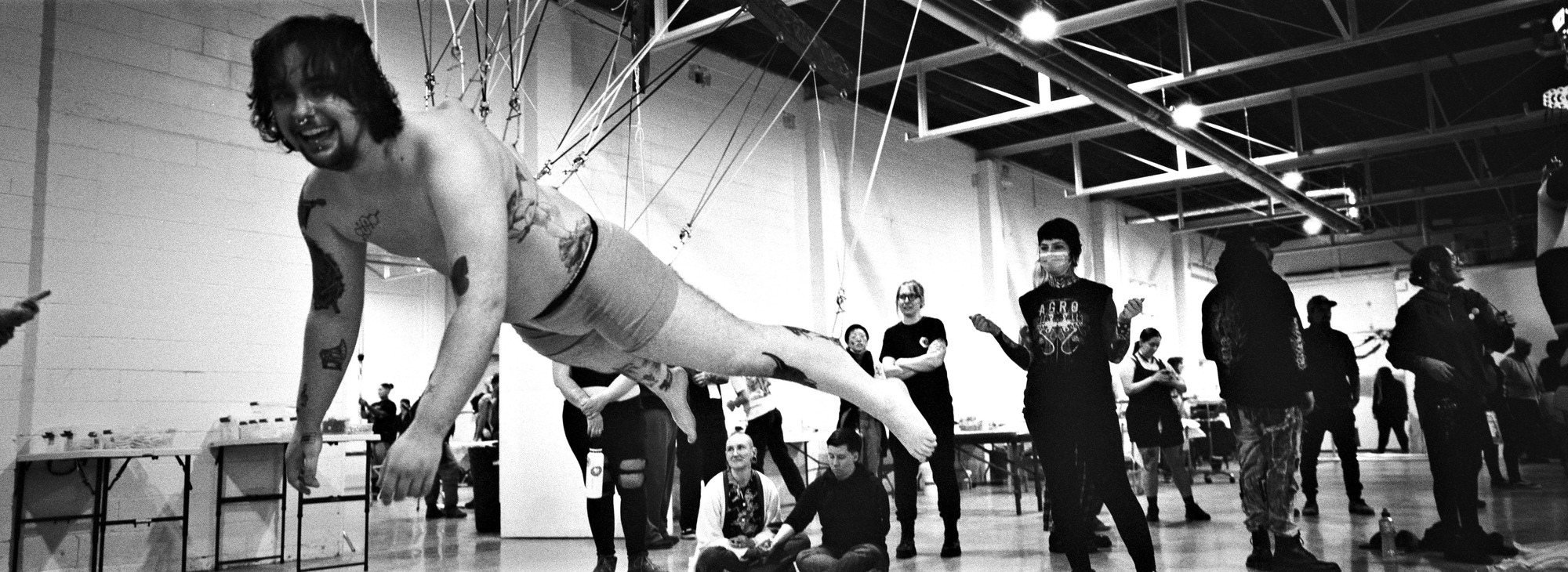

As part of his thesis on the ‘Body as Transformative Object’ Jason is looking for people involved with the body modification community who class themselves as artists. These can be either people who modify others, or who are modified themselves, surgically or otherwise, performers, suspension crews, or any others who see what they do as an art form. I am particularly interested in people that push boundaries that little bit further.

I am looking for people who are willing to take an email-based interview on their motivations, their experiences and why they see their modifications as an art form.

The thesis will be written over the period September-December of this year. All artists interviewed will be fully credited and a copy of the thesis will be given to all those taking part. Contact coldcell for further details.

Jason Oliver is currently working on his BA (Hons) Graphic Fine Art course in London, UK. His main areas of concern are ritual, body modification, and performances linking the two. He is researching social taboos and the general public’s response to direct actions onto the body and has a special interest in the use of blood, both in art and in ‘tribal’ rituals and how it acts as different signifiers depending on cultural context.

Jason Oliver is currently working on his BA (Hons) Graphic Fine Art course in London, UK. His main areas of concern are ritual, body modification, and performances linking the two. He is researching social taboos and the general public’s response to direct actions onto the body and has a special interest in the use of blood, both in art and in ‘tribal’ rituals and how it acts as different signifiers depending on cultural context.

He is an active opponent to cultural appropriation of body ritual, finding it both undermining and patronising but instead explores the role that modification plays to himself personally, without cultural references, by pushing his body into new areas of experience, with documentation being a pre-requisite.

This article was written as a precursor to his thesis, currently entitled ‘The Body as Transformative Object’. You can find Jason on IAM as coldcell.

Copyright © 2003 Jason Oliver and BMEZINE.COM. Requests to republish must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published online August 20th, 2003 by BMEZINE.COM in Tweed, Ontario, Canada.

Blake’s book, A Brief History of the Evolution of Body Adornment in Western Culture: Ancient Origins and Today is available from his website,

Blake’s book, A Brief History of the Evolution of Body Adornment in Western Culture: Ancient Origins and Today is available from his website,  The grandson of dental surgeon, noted socialite, and traveller Dr. Naomi Coval, Blake Andrew Perlingieri was inspired by his grandmother’s travels to remote tribal areas in the early to middle parts of the 20th century.

The grandson of dental surgeon, noted socialite, and traveller Dr. Naomi Coval, Blake Andrew Perlingieri was inspired by his grandmother’s travels to remote tribal areas in the early to middle parts of the 20th century.